Evolution of shrimp catching

1. Fishing weirs, nets, and traps

In North America, indigenous peoples of the Americas captured shrimp and other crustaceans in fishing weirs and traps made from branches and Spanish moss or used nets woven with fiber beaten from plants. In 1735, beach seines were imported from France and Cajun fishermen in Louisiana started catching white shrimp and drying them in the sun, as they still do today.

The Shrimp Girl by William Hogarth, circa 1740–1745, balances on her head a large basket of shrimp and mussels, which she is selling on the streets of London.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Chinese immigrants arrived for the California Gold Rush, many from the Pearl River Delta where netting small shrimp had been a tradition for centuries. Some immigrants started catching shrimp local to San Francisco Bay, particularly the small inch long Crangon Francisco rum. Fishermen dried the catch in the sun and exported it to China or sold it to the Chinese community in the United States. This was the beginning of the American shrimping industry.

Algonquin fishing with weir and spears in a dugout canoe. After a drawing by a colonist, John White (1585).

2. Trawling

Overfishing and pollution from gold mine tailings resulted in the decline of the fishery. It was replaced by a penaeid white shrimp fishery on the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts. These shrimp were so abundant that beaches were piled with windrows from their molts. Modern industrial shrimping methods originated in this area.

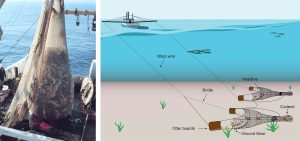

For shrimp to develop into one of the world’s most popular foods, it took the simultaneous development of the otter trawl… and the internal combustion engine. Shrimp trawling can capture shrimp in huge volumes by dragging a net along the seafloor. Trawling was first recorded in England in 1376 when King Edward III received a request that he ban this new and destructive way of fishing. In 1583, the Dutch banned shrimp trawling in estuaries.

Shrimp trawling nets.

3. Power engines

In the 1920s, the diesel engine was adapted for use in shrimp boats. Power winches were connected to the engines, and only small crews were needed to rapidly lift heavy nets on board and empty them. Shrimp boats became larger, faster, and more capable.

Modern winch. The handle is detachable to facilitate handling of the line.

Fishermen could now explore new fishing grounds thanks to the evolution of technology. Fishermen could now deploy trawls in deeper offshore waters, track shrimp and fish round the year. Larger boats trawled offshore and smaller boats worked bays and estuaries. Meanwhile, new technology advances in the 1960s, like the steel and fiberglass hulls, further strengthened shrimp boats, trawling heavier nets. Likewise, advances in electronics, radar, sonar, and GPS resulted in more sophisticated and capable shrimp fleets.

As shrimp fishing methods industrialized, parallel changes were happening in the way shrimp was processed. In the 19th century, sun-dried shrimp were largely replaced by canneries and canneries were then replaced with freezers.

In the 1970s, significant shrimp farming was initiated, particularly in China. The farming accelerated during the 1980s as the quantity of shrimp demand exceeded the quantity supplied, and as excessive by-catch and threats to endangered sea turtle became associated with trawling for wild shrimp. In 2007, the production of farmed shrimp exceeded the capture of wild shrimp.

Sources:

- Reconstructing mobility patterns of late hunter-gatherers in coastal Chiapas, Mexico: The view from the shellmounds” Barbara Voorhies, University of Colorado.

- Quitmyer IR, Wing ES, Hale HS and Jones DS (1985) “Aboriginal Subsistence and Settlement Archaeology of Kings Bay Locality” In Volume 2: Zooarchaeology, Reports of Investigations 2, edited by W.H. Adams. University of Florida, Department of Anthropology, Gainesville, FL.

- Quitmyer IR (1987) “Evidence for Aboriginal Shrimping Along the Southeastern Coast of North America” Paper presented at the 43rd Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Charleston, SC.

- Holdsworth, Edmund William H (1883) The sea fisheries of Great Britain and Ireland Oxford University.